Complex Problems vs Small Teams of Indie-Professionals

Less than six months after Boris Johnson took the prime minister office in the UK, his senior adviser and political strategist, Dominic Cummings published— on January 2nd, 2020— a new post on his personal blog. Through that post, Cummings sounded a recruiting call-for-applications for ‘unusual’ professionals. He wants these unusual and super-talented professionals to help No10 ’s small team build, test & implement strategies for complex problems that the UK faces in the new decade. Solving the complex problems also means getting to exploit the big open-to-grab opportunities at the edge of research in fields like data-science, complexity economics, network theory, and social-media communications among other promising fields. The headline read: ‘Two hands are a lot’ — we’re hiring data scientists, project managers, policy experts, assorted weirdos…”. Cummings noted in the post that his team’s goal is to tap the ‘very high-leverage ideas’ that inevitably seem bad to most people until their full-potential is unfolded.

Assorting Super-talented Weirdos

For high-authority decision-makers in business, government, or other kinds of organizations— complex problems are not an exception anymore. Rather, complex problems populate their high-priority to-solve list —from containing an epidemic or tracking terrorist-networks to patching-back a broken supply-chain network or recovering from a branding disaster on social-media.

There is an interesting characteristic that most complex problems share —they are not bound within a single discipline or domain. Interdisciplinary problems— like pandemics, climate change, terrorism— demand interdisciplinary solutions, which in turn need flexible, interdisciplinary teams to work together. When an interdisciplinary solution is created, it also brings with it the ability to capture big, intradisciplinary opportunities. All the action starts with assembling the right interdisciplinary team for the complex problem that you are tackling head-on —or the right assortment of super-talented weirdos & unusual specialist professionals with ‘high leverage ideas’. Many of the indie-professionals that I know match the above description. Martin Davidson promoted in his 2014 Bloomberg article, the case for hiring more constructively-weird people in your team to avoid group-think pitfalls and tapping counterintuitive opportunities.

Network Science and Small-Team Assembly

There is a wide variety of indie professionals that are doing interesting work out there. Before you get started on picking some of them for your interdisciplinary taskforce, I want to share with you a few insights from the world of network science.

Network science researchers study all kinds of networks —from biological cell-networks in the brain to transportation networks & social networks — and have found simple-but-powerful insights about their structure and dynamics. Noshir Contractor, a professor of behavioral sciences at Northwestern university borrowed the frameworks of network science to study team-formation in collaborative projects. In one of his research projects, he collected a massive amount of data on multi-player video-game players to study how team-formation is shaped by various pre-existing factors and which kind of teams were most successful overall. He also did this for groups of software developers and scientific-research collaborators. His work has been sponsored and used by US Army Research Lab, US Air Force Lab, and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation among many other organizations using interdisciplinary teams.

Here, I’m outlining a few of his most interesting findings on assembling the right kind of interdisciplinary team from the ecosystem, for maximizing the likelihood of project success.

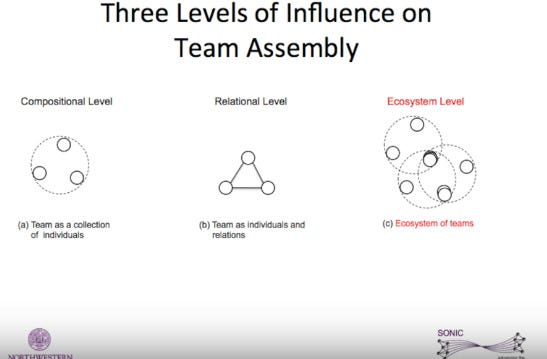

- Three key levels that influence the assembly of the right team:

-

Compositional: Which competencies you want to be included—skills and experience of individuals count here.

-

Relational: How much ‘warmth’ there is between the individuals—how much they know each other or not.

-

Ecosystem: How much overlap they have with their peers in the ecosystem, both individually and via their past collaborations.

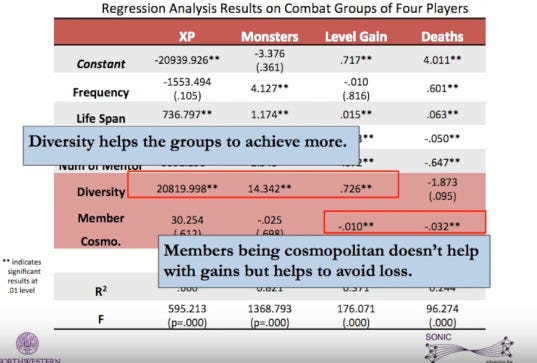

- This collaboration research found that any type of diversity helps the group to achieve more in terms of a competitive score. However, bringing cosmopolitan members (means people from completely different neighborhoods of the ecosystem) added to the robustness of the project. They didn’t let the project die in most instances— as significantly different members widen the scope of knowledge they bring and cover the structural holes(blind-spots) that homogenous teams might carry without being aware.

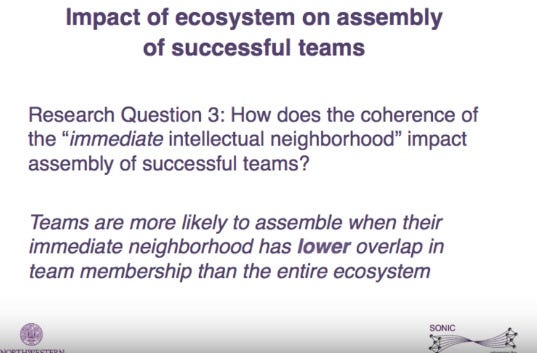

- The coherence of the ecosystem matters too. Too little global-overlap between team members means the project will struggle to coordinate the efforts of the members. On the other hand, too much local-overlap between members means no significant differences that would spark innovation by combining their skills and perspectives. In Noshir Contractor’s research, successful teams were more likely to be incoherent-locally but coherent globally in the ecosystem—this means that their members share some indirect level of connectedness (e.g: same location or same language) across the network but do not closely-match each other in their attributes like skills, background, and experience.

Free-Agency and Assembly Decisions

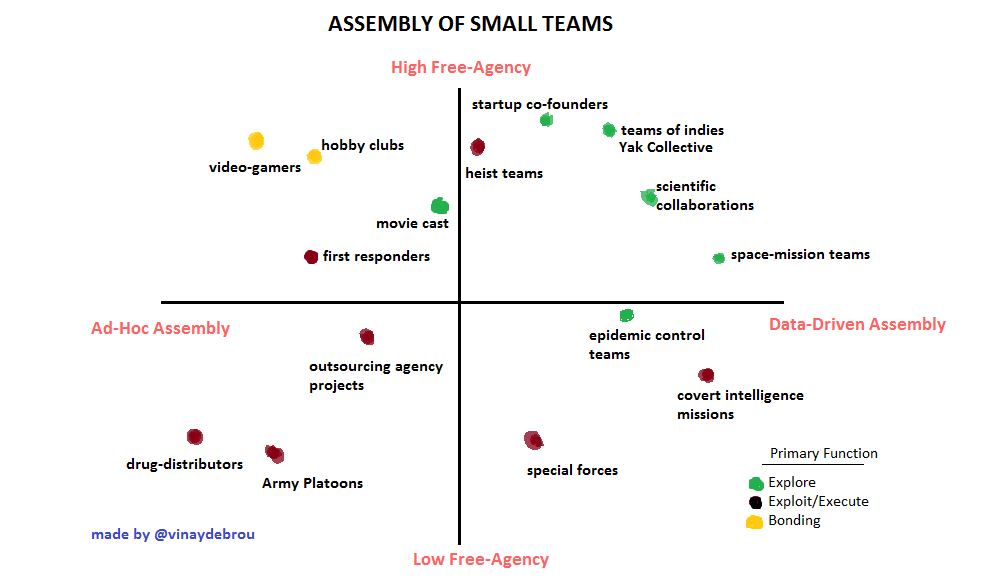

Small teams are assembled together in many different contexts for different functions. Two key variables involved in the assembly process are:

-

Level of free-agency of individual members

-

Basis of decision-making in the assembly process

In this 2x2, I’ve roughly situated the instances of small-teams in various contexts. Exploration-focused teams usually have higher free-agency, as they are involved in dealing with more complex problems without an easy and straightforward solution.

On the other hand, most execution-focused projects, especially the ones with abundant human resources(drug-distribution, army platoons, outsourcing agencies) don’t invest in a decision-making process based on collecting data about the unique capabilities and experiences that individual members bring with them. High-stakes projects with high cost-of-mistake (space-missions or epidemic control teams) tend to prioritize data-driven assembly.

There are some teams/groups/clubs made with primary motivation other than exploration or exploitation/execution. Video-gamers and hobby clubs are two such examples whose primary motivation to form a small, tightly-knit group is bonding.

Yak Collective

A good example of an ecosystem of indie professionals creating collaborative, interdisciplinary work by assembling consultants, creators, and specialist freelancers is Yak Collective. It a loose network of 200+ independent professionals (including me) who collaborate on group projects to solve interesting complex problems for organizations of all sorts—business, research, non-profit, or government. We recently released a public report —Don’t Waste the Reboot— a collage of 25 provoking ideas/frameworks contributed by 21 independent professionals from different industries, backgrounds, and skills. If you’re intrigued by the idea of working with a small, interdisciplinary team of indie-professionals custom-assembled for dealing with a complex problem your organization is facing, feel free to check out this report and more about the Yak Collective on the website. If you know someone who’d be delighted to work with or join the Yak Collective, forward to him/her this post or the link to the report.

Acknowledgments

The research-findings included here, along with the images used, are sourced from Noshir Contractor’s presentation Unleashing intellectual insights in big data at the University of Michigan School of Information(UMSI). You can find more of his work here.

Enjoyed reading this? Why not share it with someone who’ll be delighted to read this?

Back to Writings page

My Newsletter: Daybrew's Note

Join my newsletter to stay updated with what I'm working on: