What in the Small-World is this?

In addition to being a network, a small-world network structure is defined by two characteristics—

-

It has clusters.

-

Clusters have multiple links between themselves to enable the cross-cluster flow.

Clustering: Homophily—a tendency of similar nodes (eg: people with similar attributes) in the network to stick together and a bit away from those dissimilar to themselves, is the driving force behind clustering. This is why teens hangout online in a separate cluster (Snapchat), and the parents hang out separately(Facebook).

Cross-Cluster Links: This is where a small-world network shines over other network structures. Links between clusters mean that the clusters have porous gates. This enables things-that-work or things-that-overwhelm to flow over to other nearby clusters. While clustering provides enough efficiency in good times, this cross-cluster linking provides the robustness to the whole network in the face of uncertainty. This robustness comes from the flexibility that these cross-cluster links provide to the network in reshaping as and when the need arises.

Small-World Brain Networks & Dynamics of Learning

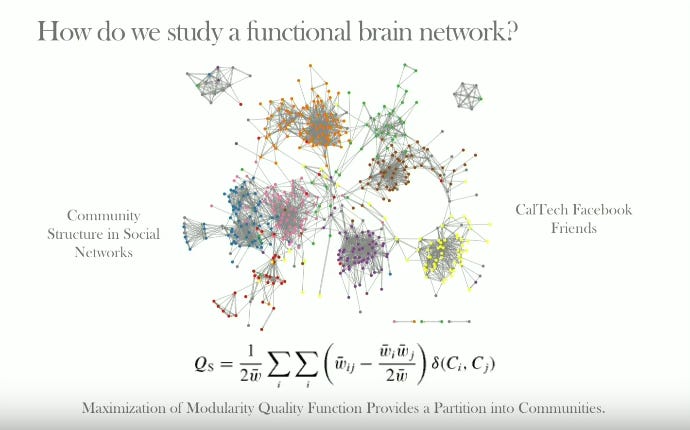

Danielle Bassett is a network-neuroscientist who took a look at the structure of the brain’s functional areas from the lens of networks. She was interested in finding out if the network structure of brain cells plays a key role in the process of learning. And if it does, what kind of network structure does the brain uses for learning and how it evolves during the process.

Image Source: Danielle Bassett’s community lecture: Networks thinking themselves

She constructed the electrical-activity snapshots from lots of MRI scans and analyzed the patterns that emerged. The cells that were involved in similar functions—like those active for motion or those active for vision or those who are active during standby default mode —were clustered together and there were plenty of cross-cluster links. It seemed to be structured very much like a small-world network.

Cluster Flexibility —> Learnability

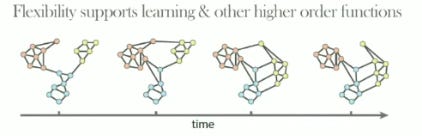

The interesting part of the small-worldness of the brain cell networks was the dynamics that enabled. In learning-process experiments, Bassett noticed these clusters were flexible and shifted their shapes according to their functional needs. It appears that the small-world structure optimizes the learnability of the network.

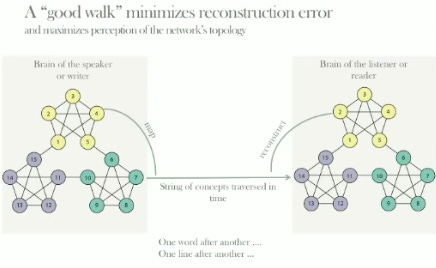

Look at these clusters forming cross-connections over time during the learning process. In Bassett’s experiments, more flexibility in network modules(clusters) predicted individual differences in visuomotor learning, cognitive flexibility, working memory, planning& reasoning, and learning rate. This is revealing and an exciting finding. This flexibility is not random. It turns out that the brain emulates the architecture to that of the object of learning. The knowledge objects like a lecture, paper, or a book that are most optimal for a knowledge-transmission via linear walk-throughs(reading or listening) have a meta-structure like a small-world network. This is helpful to an author for accurate and efficient mapping(compressing) and to a reader for reconstructing(uncompressing) with minimal loss of knowledge.

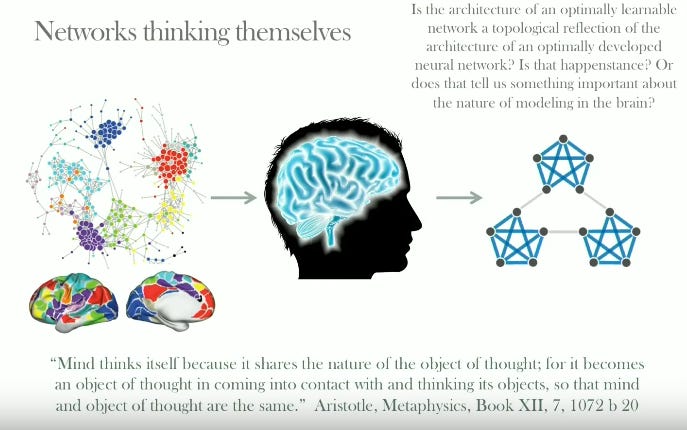

These findings have popped interesting questions across the domains of learning, engineering, neuroscience, psychology, physics, and art. The most important question: Does small-worldness enable networks to think and evolve by themselves?

Image Source: Danielle Bassett’s community lecture: Networks thinking themselves

Acknowledgments

These ideas and images come from the stellar work of Danielle Bassett over many years and her 2019 Community Lecture at Santa Fe Institute — Networks thinking themselves. If you’re interested in diving deeper, check out her work at Complex Systems Lab of University of Pennsylvania.

Liked this note? Why not share it with someone who’ll be delighted to read this?

Back to Writings page

My Newsletter: Daybrew's Note

Join my newsletter to stay updated with what I'm working on: